A History of LGBTQIA+ and Pride Month Marketing

- Why Do We Celebrate Pride Month During June?

- 1920s-1940s

- The Roaring â20s

- The Great Depression

- World War II

- What did LGBTQIA+ marketing look like in the 1920s, â30s, and â40s?

- 1950s, â60s and â70s

- The Homophile MovementÂ

- The Lavender Scare

- The American Psychiatric Association

- Executive Order 10450

- Cooper Do-nuts Riots

- 3 Key Protests and Uprisings of the â60s Before Stonewall

- Stonewall Uprising

- Christopher Street Liberation Day

- The Birth of Pride

- âOur job as gay people was to come out, to be visible, to live in the truth, as I say, to get out of the lie. A flag really fit that mission, because thatâs a way of proclaiming your visibility or saying, âThis is who I am!ââ

- - Gilbert Baker

- What did LGBTQIA+ marketing look like in the â50s, â60s and 70s?

- The 1980s and â90s

- ACT UP

- World AIDS Day

- Defense of Marriage Act, 1996

- Matthew Shepard

- 1999: Official Establishment of Pride Month

- What Did Pride Month Marketing Look Like In The â80s And 90s?

- 2000-2010s: Pride Month Marketing Goes Mainstream

- Pride Month Marketing Today

- Understanding History Makes For A Better Future

For more than 50 years, Pride celebrations — parades, festivals and marketing campaigns — have staked a large, colorful claim in the month of June. And for a very good reason.

June holds a significant place in the hearts of the LGBTQIA+ community, and to understand the present, we must understand the evolution of Pride Month marketing, why we celebrate Pride Month, and revisit how it all began.

Why Do We Celebrate Pride Month During June?

Pride Month encapsulates the ongoing struggle for equal human rights.

One of the foundational moments marking Pride’s emergence occurred in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969 at The Stonewall Inn in New York City (more on that later).

The Stonewall uprising was unarguably a major turning point for LGBTQIA+ peoples’ liberation, but it was neither the first nor the last, but one in a long series of pivotal events. The uprising was commemorated during the first pride parade on June 28, 1970, in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Pride parades are an integral part of LGBTQIA+ culture, and people around the world continue to march in solidary and in remembrance of Stonewall every June.

For decades, the LGBTQIA+ community stood bravely to oppose violence and unjust laws against their people.

Let’s take a trip back in time.

1920s-1940s

The Roaring ‘20s

Three trans women and a man dancing at a nightclub, circa 1927.

Source: Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images

While the US media’s first documented portrayal of LGBTQIA+ people could be seen in the 1894 Dickson Experimental Sound Film—more famously known as The Gay Brothers—the roaring ‘20s saw more representation of LGBTQIA+ folk in art and media.

Lesbian/gay/bisexual/gender non-conforming and trans people had a major presence in Chicago’s South Side and in New York City (see: Gay New York by George Chauncey, 1940.)

With the economic boom of the roaring 20s came a time of normalized sexual liberation and less rigid gender expression. LGBTQIA+ performers with different intersectional identities made their presence known in various nightclubs in Chicago, New York and across the US, allowing for the growth of connections and the beginnings of a large network of friends, chosen family and opportunities for romantic partners.

And in 1924, Chicago-based army veteran Henry Gerber started the Society for Human Rights, the USA’s first LGBTQ+ rights organization.

The Great Depression

The 1929 stock market crash kicked off The Great Depression, a stark contrast to the lively years that preceded it. Whereas the ‘20s saw a rise in acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community, the ‘30s saw a shocking reversal.

The same cities that once revered LGBTQIA+ culture began to abhor it; as rigid gender roles were prioritized, many felt like the existence of the community threatened the framework of the “traditional” family.

The rise in “phobias” against the LGBTQIA+ community was completely rooted in marketing and propagandist efforts. “Breadwinning” men, downtrodden by losing their jobs and struggling to provide for their families, took to finger-wagging and even led the charge of police brutality against the LGBTQIA+ community.

World War II

By the ’40s, one could be subject to jail, losing their kids, or even be forced to receive hormone injections and shock therapy to “curb homosexual desires.”

During this time, homosexuality was considered a mental illness, and was treated akin to depression and anxiety disorders. When psychologist and UCLA-tenured professor Dr. Evelyn Hooker was befriended by a group of gay men, the stark contrast between Hooker’s readings and what she’d experienced vastly differed.

After recruiting a group of researchers to conduct a study on gay men, Dr. Hooker found that gay men showed absolutely no cognitive difference from their heterosexual counterparts, debunking the psychological diagnosis that they were mentally ill.

It wasn’t until the 1950s, however, that Dr. Hooker’s findings were seen by the public eye.

What did LGBTQIA+ marketing look like in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s?

Look, marketing to LGBTQIA+ people wasn’t really common throughout these decades.

While the nightlife and community-wide existence of LGBTQIA+ folk was the worst-kept secret ever, it was the grassroots campaigning and PR against laws that prevented open discussion of homosexuality in art, mainly on stages where LGBTQIA+ people performed, that changed the game.

As a matter of fact, more marketing was done against the LGBTQIA+ community than in its favor. The community’s historical presence, contributions and creation of art during these very different decades was, however, undeniably significant.

While the 1920s were a time of liberation, there were still multiple laws that prohibited the open presence of LGBTQIA+ people in society.

As the rigid “phobias” of the Great Depression bled into the WWII era, LGBTQIA+ people were subject to assault, ridicule and inhumane treatment by cisgender, heterosexual people, including widespread mistreatment at the hands of police. And this worsened in the decades to come.

1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s

As “gay entrapment” ran rampant in NYC and other major U.S. cities (more than 50,000 men had been arrested for “disorderly conduct” by the ‘60s), further propaganda, marketing efforts and discrimination against the LGBTQIA+ community ensued.

The Homophile Movement

In November of 1950, a group of LGBTQIA+ activists founded The Mattachine Foundation, America’s first national gay rights organization. By secretly publishing and distributing a review, the foundation worked to eliminate bigotry and help at least push for some form of acceptance.

This marked the beginning of The Homophile Movement, the very foundation of the Liberation Movement.

The Lavender Scare

You’ve heard of McCarthyism and the 2nd Red Scare of the 1950s, but you may not have heard of The Lavender Scare, another witch hunt that went on in conjunction with the famous fear of communism.

The Lavender Scare followed a covert investigation of numerous governmental employees during the beginning of the Cold War.

In December of 1950, Senate propaganda titled Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government was handed to numerous members of Congress.

As a result, a combined 4,800+ LGBTQIA+ people were fired from their government jobs and discharged from the military.

The American Psychiatric Association

In 1952, the APA listed homosexuality as a cluster B antisocial personality disorder in its first-ever publication of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, despite a glaring lack of any empirical or scientific data.

This helped fuel propaganda and marketing efforts against the LGBTQIA+community for the remainder of the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and beyond.

Executive Order 10450

A year after the APA’s categorization of homosexuality, President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which banned LGBTQIA+ people from being federal employees in any capacity. It listed LGBTQIA+ people alongside alcoholics and mentally ill people as security threats.

Cooper Do-nuts Riots

Cooper Do-nuts, LA

Source: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries

It all started at a donut shop.

It’s May of 1959 in Los Angeles, California. Stonewall hasn’t happened yet, and it won’t for another 10 years. Transgender people seek solace at Cooper Do-nuts.

When police enter the coffee shop and arrest five people, the response is unlike any other: Shop patrons flood the street, dancing on cars while throwing their coffee and donuts into the air. What they start is documented as the first queer uprising of the 20th century.

In the years following, numerous other coffee shop uprisings occurred around the U.S. Like Cooper, these shops became symbols of LGBTQ+ sanctuary.

3 Key Protests and Uprisings of the ‘60s Before Stonewall

The Cooper Do-nuts riot sparked multiple uprisings and protests against government, police and societal discrimination, erasure and violence against members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Like it or not, protest is itself a form of guerilla marketing and grassroots PR.

Now, let’s talk about the events that really set Pride in motion.

1. 39 Whitehall Picket

New York City, New York

In 1964, what’s documented as the first organized demonstration for gay rights took place in downtown New York City. Gay men were rejected for service in the Army, then outed publicly.

A group led by the Sexual Freedom League picketed at the Armed Forces Induction Center — but it would be another 47 years until LGBTQIA+ people could outwardly enter the military.

2. Council on Religion and the Homosexual Ball

San Francisco, California

Known as the Stonewall of San Francisco, the Council on Religion marked a stark change and alignment between SF’s LGBTQIA+ community and clergymen. It was essentially a drag ball held to entertain and connect with religious figures who held heavy influence, but was still met with resistance by police.

After ball attendees were still arrested despite conversations with the SFPD, clergy leaders held a press conference the following day on January 2, 1965 to publicly condemn the ongoing police harassment of LGBTQIA+ people.

3. Dewey’s Lunch Counter Sit-In

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

After Dewey’s — a Philly-based burger joint — began refusing service to “homosexual-presenting” people following an “unruly” encounter with a group of non-conforming teens, the Janus Society helped stage a series of sit-ins to protest the restaurant’s homophobic actions.

After a few arrests, pickets and another sit-in, the Janus Society’s sit-in — the first of its kind — worked.

Across the U.S., various sit-ins, protests and riots ensued following the mistreatment of LGBTQIA+ individuals. Unknowingly, in the midst of a huge movement, there was one uprising that completely changed the game.

Stonewall Uprising

Greenwich Village, New York City

The Stonewall Inn in 1969.

Photo Credit: Newsweek

The best marketing tactic is word of mouth, a genuine cause and a brick… or a punch… or a Molotov cocktail — at least in the liberation movement’s case.

The story of the Stonewall Inn is not too different from Cooper Do-nuts, but it was longer in scale. While the Cooper Do-nuts “riot” lasted three days, the uprising at Stonewall went on for nearly a week.

At the time, New York state law revoked bars’ liquor licenses if they were caught selling alcohol to LGBTQIA+ individuals, and police would do routine checks on Christopher Street and in other LGBTQIA+ hubs around the city to ensure this wasn’t happening.

It was commonplace for police to ask trans people for their IDs; when they saw that their deadnames and ID photos didn’t match their current presentation, they would assault and arrest them. Anyone who was seen in any way as non-conforming — gay men, lesbian women, queer people — would be handcuffed and taken away.

When a Black, butch lesbian woman named Stormé DeLarverie — a key figure in the liberation movement — was assaulted and cuffed by an officer, she fought back, and asked bystanders why they weren’t doing anything to help.

That’s when the fighting broke out in the morning hours of June 28, 1969. People took to Christopher Street and the surrounding area of Greenwich Village. They brawled with police, threw things and protested the oppression they’d faced their entire lives. Something had to change.

Stonewall is documented as the first major LGBTQ+ uprising, but it was really just a breaking point. Unfair, violent policing, economic exploitation and discrimination came to a head here.

It’s also extremely important to remember that those who rioted at Stonewall were mostly Black and Latinx LGBTQIA+ people. For the sake of intersectionality and for discussions about race, sexuality, marketing campaigns and beyond.

Christopher Street Liberation Day

New York City

A photo of the first Pride Parade in 1970.

Photo credit: Time Out

Exactly one year after Stonewall — June 28, 1970 — the first Pride Month parade commenced, but it wasn’t what today’s parades look like. It involved a group headed by Craig Rodwell — a key figure in the LGBTQIA+ liberation movement — and they marched. This set the precedent for Pride Month, and the official Pride Parade in New York.

Stonewall had changed things, but acceptance, liberation, and equality needed (some would say still needs) to happen. LGBTQIA+ people shouldn’t have had to live in fear of their lives, losing their jobs, or facing wrongful imprisonment. This act of protest, of celebration, of risk, even, was the rawest form of marketing there is.

The Birth of Pride

You’ve heard of Harvey Milk. Sean Penn famously won an Oscar for playing him in Milk, but did you know that the first openly gay elected California official urged artist Gilbert Baker to design the first Pride Flag in 1978. The movement needed a symbol, one that represented the community and the struggles they’d faced, and Baker delivered.

“Our job as gay people was to come out, to be visible, to live in the truth, as I say, to get out of the lie. A flag really fit that mission, because that’s a way of proclaiming your visibility or saying, ‘This is who I am!’”

– Gilbert Baker

What did LGBTQIA+ marketing look like in the ‘50s, ‘60s and 70s?

In the 50’s, LGBTQIA+ campaigns were less rainbow-washed advertisements, and more covert advocacy and PR campaigning by LGBTQIA+ people, unfortunately.

Much like the years preceding, more marketing and propaganda efforts were created against the community, which had decades-long ramifications. This lasted well into the 1960s.

In the ‘60s, Pride Month campaigns looked like protests, sit-ins, boycotts and uprisings.

As the LGBTQIA+ community reached a breaking point when it came to oppression and violence, there was, of course, room for continued PR and earned media work, but the on-the-streets activism is what really got the ball rolling for the Liberation Movement.

In the ‘70s, Pride Month campaigns looked like heightened activism. Though the Stonewall uprising was remembered annually, Pride Month had not quite been solidified as a concept in the popular mind or in marketing.

The 1980s and ‘90s

The LGBTQIA+ community was rocked to its core in the ’80s. Things had come a long way since Stonewall, but an even bigger threat was emerging — one that’s led to further stigma against the community, even to this day. The HIV and AIDS pandemic placed a target on many LGBTQIA+ people’s backs.

ACT UP

Source: The New Yorker

In a country where the president and his team were caught laughing at victims of HIV, the church condemned those who suffered and outrageously expensive medications prevented patients from getting the treatment they needed, the pandemic raged on and took millions of lives.

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, was an action group founded in 1987 to push government leaders to lower the cost of medications, speed up the process of FDA approval and actually bring in people suffering from HIV and AIDS to trial these medications.

Through grassroots marketing and guerilla protests like “die-ins” conducted in churches, ACT UP’s advocacy pushed medication trials forward, saving lives and starting a major shift from stigma to acceptance regarding the pandemic.

World AIDS Day

Since the start of the HIV pandemic in 1981 (people were unknowingly infected as early as the late ‘70s), more than 32.7 million people have died.

A year after ACT UP’s founding, the World Health Organization designated December 1, 1988 as the first World AIDS Day. This offered the worldwide opportunity for people to band together to raise awareness of and fight against the pandemic that killed millions.

Defense of Marriage Act, 1996

Same-sex couples had brought individual lawsuits to state governments since the early 1970s — demanding that their marriages be legally recognized. In May 1996, Republican lawmakers Bob Barr and Don Nickles introduced the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as the union of one man and one woman — banning federal recognition of new or existing gay marriages. While it did not prohibit states from issuing same-sex marriages, DOMA allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages issued by other states. Passing both the house and senate with veto-proof majorities, Democratic President Bill Clinton signed DOMA into law in September of 1996. Clinton’s decision not to proceed with a symbolic veto was seen as a slight against the gay community that helped elect him. Clinton had stirred controversy with the community before, introducing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 1993 — a military policy banning gay, lesbian, or bisexual people from serving in the military unless they lied about their sexual identity.

The result of DOMA: gay spouses were now legally excluded from government employee and social security benefits, protections for immigrants, and the entire scope of U.S. laws designed to protect families of federal officers. Removing the gay population from financial aid eligibility evaluation and federal ethics laws put livelihoods at risk for years. Though it faced numerous lawsuits and efforts to repeal, DOMA showed no signs of crumbling until portions of it were declared unconstitutional in 2013, which opened the way for Obergefell v. Hodges two years later (more on that soon).

Matthew Shepard

Source: The Matthew Shepard Foundation

It was the early morning hours of October 6, 1998 at a bar near the University of Wyoming. Matthew Shepard, an openly gay student, accepted a ride home from two men, and would never return home.

Shepard was brutally attacked and tied to a fence, where he suffered for multiple days until dying from the wounds he sustained.

After his murderers were put on trial, vile protests from the Westboro Baptist Church organization and other violent, homophobic domestic terrorist organizations ensued.

These anti-gay protests were so severe that Shepard’s parents feared burying him, worrying that these groups would vandalize and deface his gravesite.

Shepard’s death, as tragic as it was, was something of a wake-up call for many Americans: Why do we deserve to die for living our truths? Something had to change, and that change was on the horizon.

1999: Official Establishment of Pride Month

In the last year of a tumultuous decade, President Bill Clinton officially established June as “Gay and Lesbian Pride Month.” Ten years later, Barack Obama would rename June as “LGBT Pride Month” in 2009. Most recently, in 2021, Joe Biden added “Queer” to the acronym, reestablishing June as “LGBTQ Pride Month.”

What Did Pride Month Marketing Look Like In The ‘80s And 90s?

The ‘80s and 90s saw the very beginning of brands trying to outwardly — albeit sometimes vaguely — connect with the LGBTQIA+ community. At its most upfront, these brands were met with boycotts from their heterosexual, homophobic audiences, something that bled into campaigns even in to the 2000s, onward.

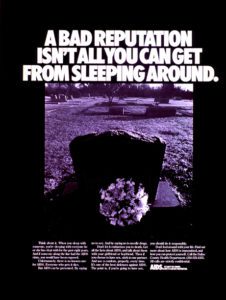

An Unknown Virus

Actual condom-oriented PSAs to prevent the spread of HIV.

Source: Dallas County Health Department

A dark rash. A cough. Fatigue. Fever. Chills. Loss of appetite. Weight loss. Thrush. Nausea. The body breaks down. One becomes weak. Bedridden, overcome with sickness.

The homophobic, Moral Majority Reagan-era officials had an anti-gay field day when the outbreak reached its peak. Their marketing campaigns called it The Gay Cancer. Ronald Regan’s communications director even called AIDS “nature’s revenge on gay men.”

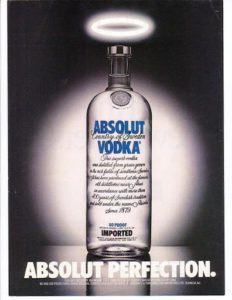

Absolut Vodka

Source: Queer Advertising

Absolut was one of the first brands to directly market to the LGBTQIA+ community.

These 1981 “Absolut Perfection” ads were served in LGBTQIA+ publications across the country, and the messaging was clear: Absolut wanted this segment to know that they didn’t see flaws or imperfections in queer identities.

This is significant for many reasons: 1) it was inclusive enough to warrant a loyal following, and 2) because they so seamlessly leaned into their allyship for years.

Absolut’s connection with the LGBTQIA+ community has lasted more than 40 years now. In 2011, they celebrated “30 years of going out and coming out,” and they haven’t stopped there.

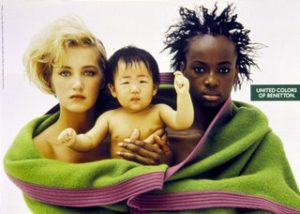

United Colors of Benetton

United Colors of Benetton’s “Blanket” Campaign, 1991

Photo: Oliviero Toscani

Fashion company Benetton has always been known for their provocative ad placements, but their 1991 “Blanket” campaign, which depicted a nude, lesbian couple wrapped holding a baby while wrapped in the titular blanket, was a true needle-moving moment for LGBTQIA+ marketing efforts.

As non-heteronormative relationships were still considered taboo and shameful, Benetton’s stance for a love that transcends gender, ethnicity and societal norms is very groundbreaking and beautiful, all at once.

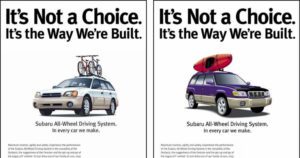

Subaru

Subaru’s mid-90s ads

Source: Lesbian News

What does a lesbian bring to a second date? According to Subaru… it’s a Subaru. Widely regarded as a lesbian-friendly vehicle for over 25 years, Subaru’s mid-’90s campaigns were successful for many reasons.

After extensive persona research, Subaru’s account planning team realized that lesbians in Northampton (MA) and Portland (OR) served as household leaders and key decision makers.

Taglines such as “It’s not a choice, it’s just how we’re built,” and “Get out and stay out” fully appealed to why this target group bought Subarus — they were durable, but not flashy.

Subaru’s stake in the LGBTQIA+ community is incredible not only because of this fearless advocacy, but also because they did some impressive geo-targeting at a time where these marketing tactics weren’t well known.

IKEA

The year after the Clinton-era “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” law went into effect, IKEA did something huge.

As more and more brands took the risk of marketing to the still highly marginalized LGBTQIA+ community, IKEA took campaigning one step further. In 1994, they aired what is famously known as the first advertising spot featuring a gay couple.

The TV commercial, which features a gay couple shopping for furniture, caused a ruckus, and continued on the path of normalizing non-heteronormative relationships.

While the spot is a masterclass in simplistic storytelling and brand advocacy, it also proves an excellent marketing deliverable, as IKEA’s planners truly did their research and found that people in LGBTQIA+ relationships tended to have more disposable income than their heterosexual counterparts.

2000-2010s: Pride Month Marketing Goes Mainstream

The 2000s-’10s saw huge improvements in the treatment of LGBTQIA+ individuals across the U.S. — and world — and marketing campaigns followed suit. While the ’90s campaigns we talked about earlier targeted the LGBTQIA+ community, messaging was vague, and nothing was crystal clear.

In the new millennium, things changed, and so did brands.

Lawrence v. Texas

Like we talked about earlier, it was illegal to be non-heterosexual in public and engage in intimate acts of the sort.

When police entered John Lawrence’s Houston, Texas apartment in response to a reported weapons disturbance, they caught him being intimate with his partner, another man named Tyron Garner. The couple was arrested for violating Texas’ “Homosexual Conduct” law. This law did not punish heterosexual couples for acting intimately.

Texas is known for its regressive policies (see: Roe v. Wade), but this one takes the cake for invasion of privacy to the point that it reveals the thin line between separation of church and state.

In a 6-3 decision — William H. Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas (remember his name) ruled in favor of the harmful prosecution, while the 6 remaining justices voted against it — the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Texas law altogether. But is it safe?

After 2022’s reversal of Roe v. Wade and Casey, Thomas mentioned the need to revisit all previous law passings that fell under due process. Only time will tell if we’re moving forward or going backwards.

Obergefell v. Hodges

The 14th Amendment has long been a protector of LGBTQIA+ people’s rights. A decade after the passing of Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court decided, in a 5-4 vote, that the right to marry was based on each individual American’s fundamental freedoms under the Due Process clause.

Obergefell was significant for many reasons: LGBTQIA+ couples could not only marry, but adopt children, obtain social security and next-of-kin benefits from their spouses, and even make medical decisions.

What did Pride Month campaigns look like in the ‘00s-’10s?

From the early 2000s-20-teens, audiences got a taste of what today’s Pride Month campaigns look like: more upfront, outward-facing and honest.

Brands began to transparently support the LGBTQIA+ community, but without fully acknowledging its unique facets and intersections. Successful campaigns were few, but this starting point marked important progress that was sure to stay the course.

Washington Mutual Thanks The Gays

Source: Sirius XM Media

This ad came out over 15 years ago, but Washington Mutual (RIP) made history by being one of the first financial institutions to take a stance in support of the LGBTQIA+ community.

While the ad wasn’t flashy or rainbow-washed, the message was clear, they were thanking LGBTQIA+ couples — see the name at the top left corner of the check — for being part of the WaMu community.

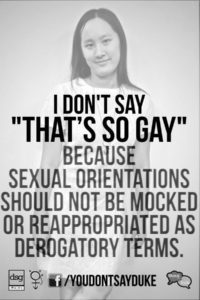

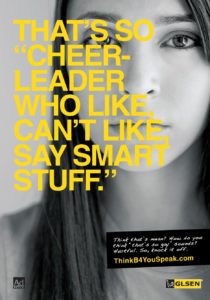

Think Before You Speak

Source: LifeHack.org

Source: LifeHack.org

Source: LifeHack.org

Remember when Hillary Duff ended homophobia in 2008 by telling girls in a store not to say “that’s so gay?” Us, too. Just kidding, but the “Think Before You Speak” campaign was iconic for many reasons.

Launched to raise awareness of the derogatory vocabulary and stigmas against LGBTQIA+ people, the “Think Before You Speak” PSAs used the analysis of hate crimes, regressive laws and rates of suicide in the LGBTQIA+ community to send a message: be a decent human being.

Never Hide

Source: HuffPost

Starting in 2007, Ray-Ban launched their Never Hide campaign, which empowered their audiences to show up in their stylish glasses. In 2012, they expanded Never Hide to reach the LGBTQIA+ community, empowering them to come out and live life as their true selves. The above ad, which shows two men holding hands in a public setting, was a subtle but sweet start to what would be a decade of aggressive campaigning toward the LGBTQIA+ community.

Pride Month Marketing Today

We’ve reached an age where Pride Month campaigns are bountiful. Some are good, and others are… not so good.

From Apple hiring its first openly gay CEO and creating amazing Pride Month ads to Nike serving body-positive and intersectionality-forward Be True products to Target’s tasteful Take Pride campaign, brands are starting to get the memo.

Inserting your brand into Pride Month is a beautiful idea in theory; but in practice, it has to give back, and make a statement that’s inclusive of all members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

And from the looks of it, we’re getting there. But there are still plenty of stumbles.

Bud Light faced recent controversy when it included trans actress Dylan Mulvaney in an advertising campaign leading up to pride month 2023. Backlash from anti-trans customers was explosive — and public. Target, a company widely known for its pride merchandise collection and generally positive attitude toward queer people, has taken two steps backward — relegating its pride collection to the back of many stores (or hidden it altogether) due to threats by homophobic customers.

Still, some brands remain unwavering in their support. This year, Visible by Verizon launches its year-long support of Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders (SAGE) — helping to combat loneliness for LGBTQ+ elders by driving conversations between groups like The Old Gays and younger generations of queer people online.

Tinder has introduced five new profile stickers that help LGBTQIA+ daters connect with each other more easily. Lime has recently adorned scooters in metropolitan cities around the world with rainbows, as it donates to local queer organizations.

Understanding History Makes For A Better Future

Pride Month marketing has come from self-defense PR to brands doing Pride Month right – and wrong.

But once you understand the very importance of history and how it plays into Pride Month, you can better understand the importance of inclusivity, intersectionality and diversity when it comes to your campaigns and the LGBTQIA+ community.

Know your history, and know to trust an agency that takes all of this into account when building your Pride Month and afterward.

Contact us today so we can help you get started.